Ruby-throated Hummingbird Migration

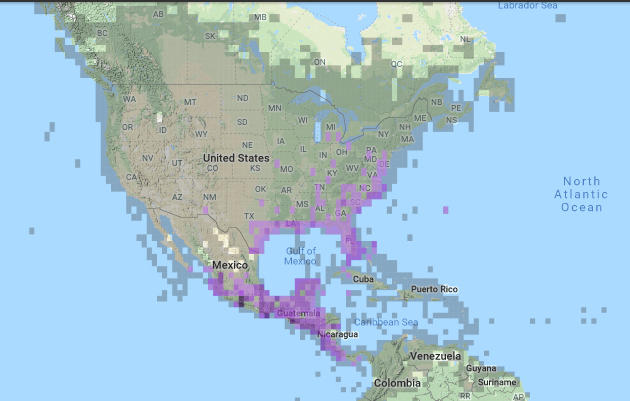

Most Ruby-throated Hummingbirds winter between southern Mexico and northern Panama (as seen by the concentration of purple on the Ebird abundance map). They begin moving north as early as January, and by the end of February most are at the northern coast of Yucatan, gorging on insects to add a thick layer of fat in preparation for flying to the U.S. Before departing, each bird will have nearly doubled its weight.

Most Ruby-throated Hummingbirds winter between southern Mexico and northern Panama (as seen by the concentration of purple on the Ebird abundance map). They begin moving north as early as January, and by the end of February most are at the northern coast of Yucatan, gorging on insects to add a thick layer of fat in preparation for flying to the U.S. Before departing, each bird will have nearly doubled its weight.

Males depart the Yucatan first. Northern migration is spread over a three-month period, which would prevent a catastrophic weather event from wiping out the entire species. Hummingbirds have their own internal schedule, so "your" birds may arrive early, late, or anywhere in-between.

Unlike larger birds, hummingbirds are too small to benefit from traveling in each other’s wake, so flying solo works best for these tiny creatures. Hummingbirds normally travel during the day and rest at night. Unlike geese, hummingbirds typically fly low, not much higher than rooftops and the treetops, in search of food along the way.

Some will skirt the Gulf of Mexico and follow the Texas coast north, while most cross the Gulf of Mexico. Capable of flying at speeds of up to 35 miles, the trip of 500 miles will takes 18-22 hours depending on the weather. Contrary to bird lore, hummingbirds may fly over water in mixed flocks of other bird species, but they do not "hitchhike" on other birds.

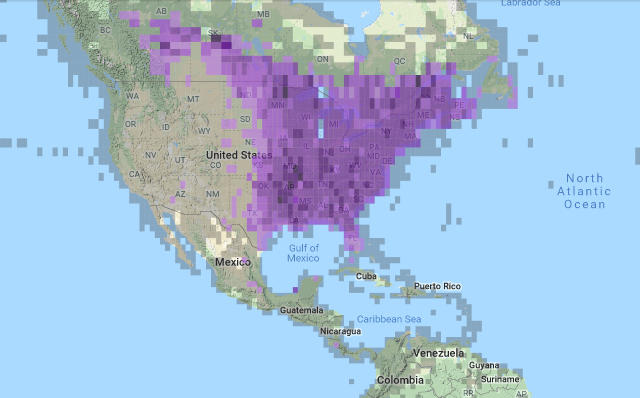

The Ruby-throated Spring Migration Map will show hummingbirds in our area as early as mid April so we recommend having your feeder out at that time. However most of 'our' hummingbirds do not show up in the area until early May. Northward migration is complete by late May. Banding studies show that each bird tends to return every year to the same place it hatched, even visiting the same feeders.

The Ruby-throated Spring Migration Map will show hummingbirds in our area as early as mid April so we recommend having your feeder out at that time. However most of 'our' hummingbirds do not show up in the area until early May. Northward migration is complete by late May. Banding studies show that each bird tends to return every year to the same place it hatched, even visiting the same feeders.

Since hummingbirds are carnivores as well (nectar is the fuel to power their flycatching activity), and depend on insects that are not abundant in subfreezing weather, they must retreat back "home" to Central America in the winter or risk starvation. However, a few Ruby-throated remain along the Gulf coast each winter instead of continuing to Central America.

Unlike the Rufous and other hummingbirds of the western mountains, where freezing nights are common even in summer, Ruby-throats aren't well adapted to cold temperatures. Mother Nature has equipped them to withstand the unexpected, however. If a cold snap sets in early, hummingbirds go into a state called torpor. Their little bodies will basically shut down all non-essential functions, their temperatures drop by up to 50 degrees, and their heartbeats slow to almost a stand still. A hummingbird in torpor state will often hang upside-down from a tree or feeder, so don’t be alarmed if you see this; they will “wake up” and be about their journey once the weather warms up a bit. The northern limit of this species coincides with that of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker; if the earliest males arrive before sufficient flowers are blooming, they raid sapsucker wells for sugar, as well as eat insects caught in the sap.

Adult males may start migrating south as early as mid-July, but the peak of southward migration for the males is late August and early September. Immature Ruby-throats of both sexes look much like their mothers. Young males often have a "5 o'clock shadow" of dark throat feathers in broken streaks, and many develop one or more red gorget feathers by the time they migrate. Immature females may have much lighter streaks in their throats, but no red. By early October all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are migrating.

The urge to migrate is triggered by the shortening length of sunlight as autumn approaches, and has nothing to do with temperature or the availability of food. For a hummer that just hatched, there's no memory of past migrations, only an urge to put on a lot of weight and fly in a particular direction for a certain amount of time, then look for a good place to spend the winter. Once it learns such a route, a bird may retrace it every year as long as it lives.